Breaking boundaries: the Climate Justice Caravan

BY JOÃO CAMARGO

This spring, climate and social justice movements in Portugal, Ireland and Turkey set off to walk in climate justice caravans throughout their territories. They knocked at the doors of great emitters and visited the frontlines of climate struggles. These movements got in touch with thousands of people in places they usually don’t travel to, discussed face-to-face with communities they are usually not in the least engaged with, committed to a form of militancy that required very high levels of commitment, and established unequivocal bonds for future action and organisation.

We need to build a strong movement to rupture the old ways. The boundaries set within new social movements and the western part of the climate justice movement need to be broken. We have a clear portrait of the environmental movement of the last thirty years. And only if we purposefully deconstruct the idea of a young, urban, educated and white middle class climate justice movement can we build a mass movement that is sustained in the medium-term.

Capitalism has always used the civilization-old rule of dividing to conquer, of dominating and solidifying hierarchies between ethnicities, genders, geographies, communities and groups. In opposition to that many have used the idea of a working class that can confront and abolish these hierarchies and divisions, allowing the formation of social majorities that can force the overthrow of capitalism.

Of course the divisions have existed and been fuelled by all elites well before the advent of capitalism. In particular, the rift between city dwellers and rural workers and peasants has been an essential social division in history. But it was profoundly aggravated by the industrial revolution. Indeed the undervaluation of rural communities and their full integration in the world of commodities provided the human strength that established capitalism.

Many from these communities were uprooted from their meagre rural dwellings and brought to cities. There they were pitted against older urban communities to guarantee

the race to the bottom of low wages and terrible life and work conditions. This was the only way to go to allow maximum profit.

Living miserable lives in slums, sweatshops and industrial death traps, uprooted rural communities were the backbone of the workers’ movement. Their communal organisational structures were combined with industrial discipline to give form to the socialist movement that swept and changed the world in the 19th and 20th century. These were the people Marx referred to when he said that proletarians had nothing to lose but their chains.

Simultaneously, the metabolic rift between the countryside and the cities, with a permanent flux of energy, nutrients and people into ever-growing metropolis, is at the base of environmental degradation in successive crises.

In the revolutionary processes of the past, the alliance or division between rural communities and urban workers was an ever present issue. Yet rural exodus is a global reality andthe countryside is becoming a disempowered, overexploited and forgotten part of territories. However, the countryside covers the majority of land, and in many countries in the Global South, the majority of the populations.

Can ecosocialism work in the ultra-urbanized world? Can we sustain the permanent influx of energy and raw materials from the rural areas into big cities? And can we sustain cities with millions of inhabitants in much harsher climatic conditions? Further, can we recuperate rural territories devastated by mining, by intensive farming and animal production, by green deserts of tree plantations? Can we turn them into territories more resilient to drought, flood and forest fire?

In a highly urbanised world, when power is derived from social relations in cities and between nations, when the absolute majority of people in the Global North and Latin America live in big cities, when the rural landscape has fewer political representatives, when industries and sources of destruction, pollution and emissions are outsourced there before being outsourced to poorer countries, it is only natural that new social movements and the climate justice movement are based in cities.

And so most if not almost all the demands and politics of the climate justice movement are a program of the city, with a high focus on energy, transport, the port and the airport. International trade goes through the urban, although materially it is overwhelmingly extracted and transformed in the rural. The movement is essentially urban. It has mostly been urban. And so, a trench has been dug between our movement and rural communities.

Most of the local and national social and ecological conflicts of the climate crisis are and will continue to take place in the rural areas. It is there that the coal, oil and power plants still burn. It is there that the agribusiness model burns and emits more than ever, where mines, fracking sites, quarries, landfills and all manners of industries are. It is also in the countryside where most workers of these industries are based. Can we think of a mass social movement that has no roots in rural areas?

Caravans are rural and semi-military tactics. They are strong and powerful moments of action, where the travel and the movement of the people are notorious, building internal cohesion while reaching out.

Political caravans throughout history were often moments where an image of unity and action was projected: Gandhi’s Salt March, Martin Luther King’s Selma to Montgomery march, the march from Delano to Sacramento in California, Prestes’ Column in Brazil, Garibaldi’s Expedition of the Thousand. Even if we don’t measure the political success of these, their impact is undeniable, internally and externally. The commitment of staying many days in action, of sharing space and tasks, of approaching communities and problems outside of the regular space of action, through a humble perspective, allows for the potential growth and diversification of the movement.

The caravans used the tools of disaggregated emissions inventories to help plan their paths, passing through many of the most emitting infrastructure in each region: coal, oil and gas plants, cement and paper companies, drill sites and mines. The debate about the future of these infrastructures needs to happen right at their doorstep. Although direct actions are a useful tool to start or trigger the debates on just transition, going there and discussing what should happen there has a power of its own. When local communities and workers join this debate, the movement becomes more grounded, more connected and so more powerful.

The idea of a Climate Justice Caravan was launched by the People’s Climate Agreement (formerly known as the Glasgow Agreement) as an action to be conducted in different countries around the world. It has thus far taken place in three countries – Portugal, Ireland and Turkey.

PORTUGAL

In Portugal, the Climate Justice Caravan set off on the 2nd of April from Leirosa, near Figueira da Foz, to walk over 400km. The route was divided between two big themes: fire and water.

Starting in paper and paste mills from Altri and The Navigator Company, the caravan crossed around 200km in Central Portugal, visiting Montemor-o-Velho, Coimbra and Pedrógão Grande, a region severely affected by forest fires in the last decades, particularly in 2017. There industrial eucalyptus plantations dominate the landscape. In fact Portugal has the biggest eucalyptus area in the world, over one million hectares.

Each day there were open assemblies in theatres, in the streets, in parks and town squares, and sessions about industrial transformation in front of high emitting infrastructures. Most of the caravan was done on foot, sleeping in campsites, gymnasiums, fire stations and schools. The first ten days of the route were chosen for the theme of fire, and on the 12th of April the Caravan reached the Tejo River, in Vila Velha de Ródão, where two paper mills are famous for regularly polluting the biggest river in the Iberian Peninsula with industrial waste.

The second part of the Caravan focused on water, Participants walked, but they also took the train for free with support from the public train company, CP. They visited industrial sites, river banks where degradation was clear, and many beautiful areas.

Water scarcity and degradation of water quality are major issues with communities, and big agribusiness lobbies only think about how to opportunistically use the climate crisis. Part of that is a major project to build six more dams in the river, to create a massive irrigation area for export crops and eucalyptus.

The Caravan finished on the 16th of April in Lisbon, with a big assembly in a park next to the river. Over 40 national and local organisations, were involved in the caravan, and there were 150 participants over fourteen days.

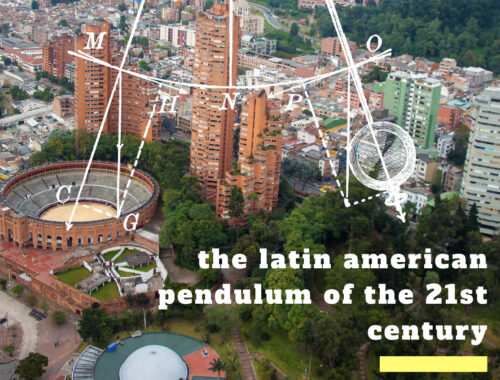

IRELAND

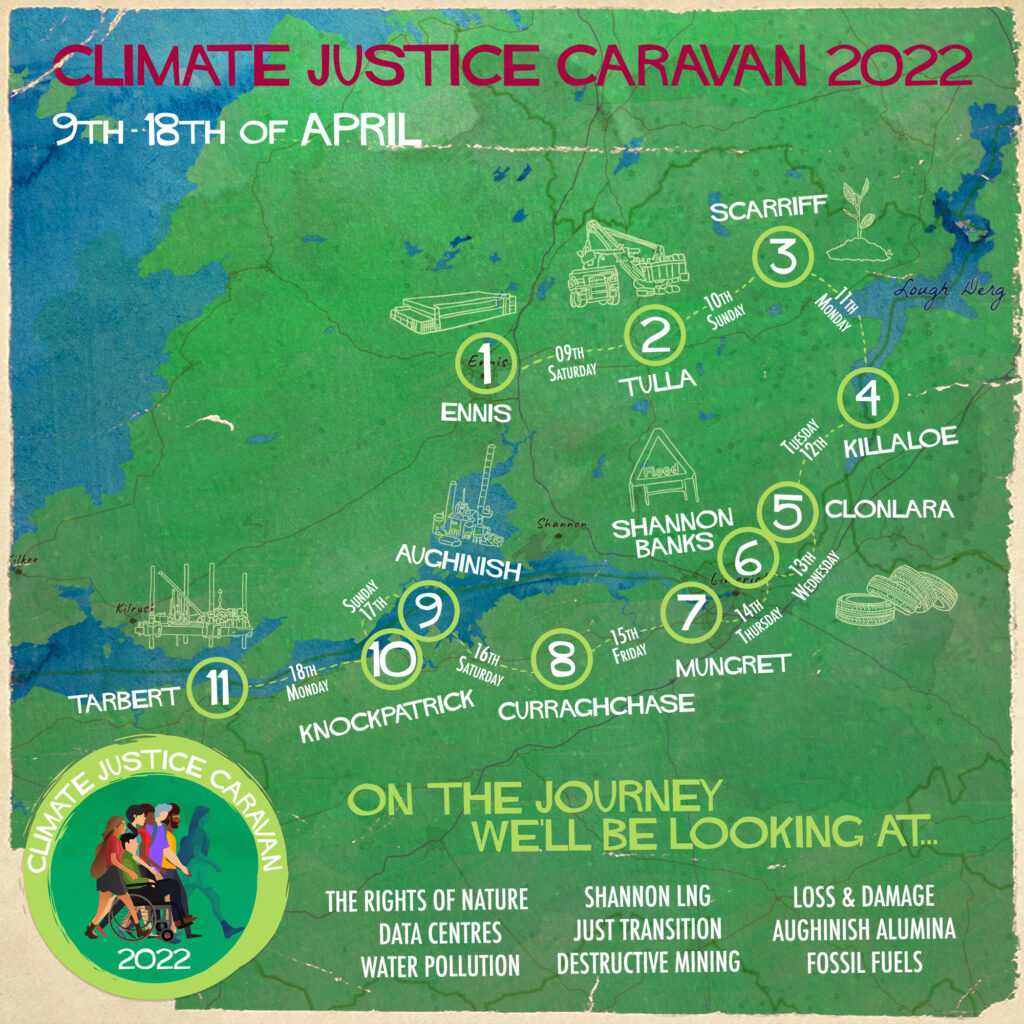

In Ireland, the Caravan ran from April 9th to the 18th, from Ennis to Tarbert and across Munster. It was composed of members from and supported by Extinction Rebellion Ireland, Futureproof Clare, Rights of Nature Ireland, Cappagh Farmers Support Group, Keep Tulla Untouched, Safety Before LNG, Friends of Ardee Bog, Ecojustice Ireland, Unite Climate Justice Group and Cultivate. Along the nine-day journey, the Caravan visited locations connected to issues such as mining and extractivism, seed sovereignty, water pollution and flooding, new data centres sites, renewable energy and energy sovereignty, loss and damage, circular economy, just transition, and predatory fossil fuel capitalism.

A key aim of the caravan was to advocate that the Shannon river be granted its own rights, as part of the national and global Rights of Nature movement. The Shannon river flows through Ireland and its importance to the communities and biodiversity that live alongside the river highlights the interconnectedness between nature and humankind. Nutrients and sediments from intensive forms of agricultural and industrial activities, untreated sewage, landfills, mining and quarrying, pesticides, and forestry activities, are destroying the river.

And the issues of flooding, particularly from the Ardnacrusha dam are growing dangerously. Despite its historical fame, currently Ireland’s woodland is less than 2% native species.

Three massively important sites were visited: the Ennis Data Centre: Rusal’s Aughinish Alumina, the biggest producer of alumina in Europe; and the projected site of a new LNG gas terminal in the Shannon estuary, a project that has been revived by the narrative of energy independence based on gas.

TURKEY

Here, the Caravan assumed a diverse format, with three different moments. On the 9th and 10th of April, over thirty participants left from Istanbul to Izmir, with other stops next to the Aegean Sea, protesting and holding forums in front of the Soma coal mine where over 300 miners died in 2015, and coal power plants. Meetings were also held with different local organisations and communities.

On the 16th and 7th of April, the caravan went from Zonguldak to Bacakkadi, where there are currently four operating coal power plants and the government plans to build two more. The group here was smaller, but many more participants joined along the way, in particular from the communities threatened with eviction.

The third part of the Caravan, from the 26th to the 29th of May was the most participated, leaving from Istanbul and visiting the Marmara region, meeting people living in settlements close to coal power plants, establishing links with active platforms in the field, and visiting local island defenders at the Burgazada islands. The Caravan was very popular, attracting a lot of attention and leading to new contacts.

Smaller groups visited other sites in the meantime. One was the the forest of Ikizkoy/Akbelen, where the government means to destroy the forest to dig for coal. Another was the Erzincan Ilic gold mine with its enormous shulphuric acid and cyanide pools that contaminate the Euphrates river.

The Caravan moved on foot, by bus and train.

Ecosocialist tactics to mend the rural-urban rift

Many seeds were planted. New coalitions were built and social forces were put in direct contact. Calls for new caravans were made, for other regions, confronting high-emitting and highly polluting infrastructures and visiting sites and communities most affected by the flamethrower that is modern capitalism.

The caravan will definitely create new campaigns, new actions, new allies. Further, it will likely create documentaries, books, and other cultural expressions that need to be spread throughout the movement and in society. We need that, we are starving for that. Other caravans might still occur until the end of the year.

The huge split between rural and urban, that sustains the influx of energy and raw materials from the rural areas into big cities with millions of inhabitants in much harsher climatic conditions, must be mended in an ecosocialist world. We need to recuperate rural territories devastated by mining, by intensive forestry, agriculture and animal production, and turn them into territories more resilient to drought, flood and forest fire, where many more people live. It is very difficult to think of a mass social movement of rupture that has no roots in rural areas. Tactics such as the climate justice caravan are needed to solidify urban-rural alliances all around the world.

João Camargo has been a political militant involved in precarious workers organization and the international anti-austerity movement in the early 2010’s. He helped create Climáximo in 2015 and has had an active role in climate jobs, anti-oil and gas campaigns, international articulation of the climate justice movement and direct action. He’s an environmental engineer and holds a PhD in climate change. He’s authored Climate Change Combat Manual and Portugal in Flames – How to rescue the forests.